Primer on the 150th anniversary of the Paris Commune – I

The PRISM editors are posting this primer on the Paris Commune (18 March – 28 May 1871), on the occasion of its 150th anniversary. We are posting it in three installments, and will soon also make it available in PDF format. We welcome comments from the widest possible range of people who align themselves with the Commune’s spirit and continuing legacy.

Part I. Historical background

This primer starts with major events that shook Europe in the 19th century and set the stage for the war that broke out between France and Germany in 1870—the Franco-Prussian War. This war directly resulted in the fall of Napoleon III and the Second French Empire, and the rise of the Third Republic—which in turn triggered a rapid chain of events leading to the Paris Commune of 1871.

1. What situation brought France and Germany to war in 1870?

From the 16th to the 19th centuries, great bourgeois revolutions had been shaking the foundations of the feudal order in Europe and North America. They had paved the way for the capitalist-led industrialization of major cities and entire countries, the gradual rise of the modern proletariat from the mass of peasants and artisans, and resultant class struggles and crises. Many governments in Europe, however, repeatedly faltered in democratic reforms, slid back to autocracy, and retained feudal vestiges.

In France, the revolution of 1789-1799 mobilized the masses of the people, especially the peasantry, to overthrow the feudal aristocracy and monarchy and to create the first French Republic. However, this first republic was cut short by Napoleon Bonaparte’s coup d’etat. He became dictator, at first as head of the Consulate (1799-1804), then as “Emperor of the French” under the First French Empire (1804-1815).

Napoleon I’s type of politics (popularly called Bonapartism) skillfully used the various class struggles in France to perpetuate his own dictatorial rule and dynasty while also building a military-bureaucratic caste that satisfied the class interests of the old and emergent elites.

Napoleon’s overreaching ambitions to expand his Empire eventually backlashed. His abdication led to the restoration of the French monarchy: first the Bourbon kings Louis XVIII and Charles X (1815-1830), followed by the “July Monarchy” (1830-1848) of the Orleanist King Louis Philippe I. But these new regimes, unlike the ancien regime, were now constitutional monarchies. They could no longer halt the fundamental changes in French society and economy, especially the continuous expansion of capitalism and growth of the proletariat.

In 1848, revolutions swept through many European states—this time with more distinct proletarian undercurrents mixed with the bourgeois-democratic. The 1848 worker-led people’s uprisings, in most instances, were suppressed in blood and fire. At the same time, the social upheavals also put in motion the forces that placed militarist autocrats in power.

In France, the February 1848 revolution replaced King Louis Philippe with the Second French Republic. This was followed by the June 1848 worker-led people’s uprising in Paris, which ended in bloody failure. In its aftermath, Louis Napoleon Bonaparte—Napoleon I’s nephew, also known as Napoleon III—rose to power by end-1848, first as elected “prince-president” of the republic, then as dictator.

Like his uncle and namesake, Napoleon III stopped a revolution in its tracks then extended his rule to become dictator via coup d’etat in December 1851. A year later, he dissolved the Second Republic, replaced it with the Second Empire, and again like his uncle, made himself “Emperor of the French”. (Marx analyzed the 1848-1851 events in his works, Class Struggles in France and Eighteenth Brumaire of Napoleon Bonaparte.)

At that time, the map of Europe was a crazy patchwork quilt of small nations, independent provinces and blurred boundaries. Napoleon III’s own brand of Bonapartism could thus exploit the many narrow nationalist aspirations and lust for war under the banner of “liberty and order”. Meanwhile, French capitalism underwent rapid growth, economic crises and militarism, showing signs of an early transition towards imperialism.

During those decades, Germany as a nation was extremely disunited. It was fragmented into many small states, and also riven by rivalry between its two large components, Prussia and Austria. The Germans were constantly bullied by tsarist Russia in the east and by Bonapartist France in the west. Nonetheless, after the 1848 bloody counter-revolution, Germany began to consolidate under the leadership of the militarist Junkers (landed nobility), at first economically through customs unions and trade treaties, then politically.

Germany’s political unification was hindered by Napoleon III’s many interventions among its localized states. But under Otto von Bismarck, who became chancellor in 1863, Prussia regained lost territory by winning against Denmark (1864) and against Austria (1866). Bismarck at the same time succeeded in his own coup d’etat to get absolute power. Finally, a North German Confederation dominated by Prussia was founded in 1867. This signaled the rise of a unified Germany while France lost its dominant position.

Both countries—France under Napoleon III, and Prussia under King Wilhelm I and chancellor Bismarck—lusted for wars to expand their territories and made rapid war preparations. The rich Alsace-Lorraine region was among their biggest bones of contention. A relatively marginal issue (on the succession to the Spanish throne) became the convenient alibi for France to push harder against Prussia, and for Prussia’s Bismarck to further pique French warlust.

This time, a unified Germany was ready for war. Old rival Austria did not join, but was also reluctant in supporting France. (The German southern states would soon join the Prussia-led North German Confederation, turning German unification into full-blown reality.)

Within France, Napoleon was opposed, on the one hand, by a fast-rising bourgeoisie which chafed from the regime’s economic exactions and political domination. But the bourgeoisie was divided into conservative republicans, who tended to ally with those who wanted to restore the old monarchy, and the radical republicans who spoke for the lower classes. Further to the left, the regime was also opposed by the fast-growing working class, which suffered much worse—from capitalist and employer abuses, taxes, unemployment, and grinding poverty. Their sons became cannon-fodder in the regime’s wars abroad, while their socialist and radical-republican leaders were hunted down and thrown into France’s notoriously brutal prisons.

We must especially note the rapid growth of the French urban population during those decades, particularly of the industrial proletariat and other non-agrarian workers. Of the estimated 2 million population of Paris in 1869, around 500,000 were industrial workers, 300,000-400,000 non-industrial or craft workers, and some 165,000 domestics. There were also 100,000 immigrant workers and political refugees, the largest number from Italy and Poland. They were the natural, large, and highly concentrated social base of various strains of proletarian-socialist and radical-democratic political thought and groups, in Paris and a few other major cities as well.

Paris, in particular, already had a long history of uprisings by workers and lower-middle classes since the 1790s. These uprisings combined economic and political demands, with local neighborhood districts (arrondisements) organizing into communes and fighting with arms and street barricades. The term “commune” merely meant a self-governing local district and its council. But in Paris and other French cities, it invoked the peak of revolutionary action by the masses as what happened in 1793, 1830, and 1848.

Amid the growing political ferment, incipient mass-based political parties (“clubs” or “societies”) rapidly grew in number, influence, and revolutionary activism. These espoused various trade-union and socialist platforms, especially the hundreds of local groups across France that eventually joined the (First) International.

During the last years before the Paris Commune, Napoleon had amnestied political prisoners and loosened up on public meetings. Thousands of such meetings were held from 1868 to 1870, enabling various revolutionary groups to influence their content and growth. When the Franco-Prussian War broke out, public meetings were banned, but the more militant “Red Clubs” took their place. Thus a vigorous mass movement continued all the way through the siege of Paris, providing physical and organized rallying points for the people to rapidly disseminate and respond to the daily events.

2. How did the Franco-Prussian War lead to the French defeat and collapse of the Second Empire?

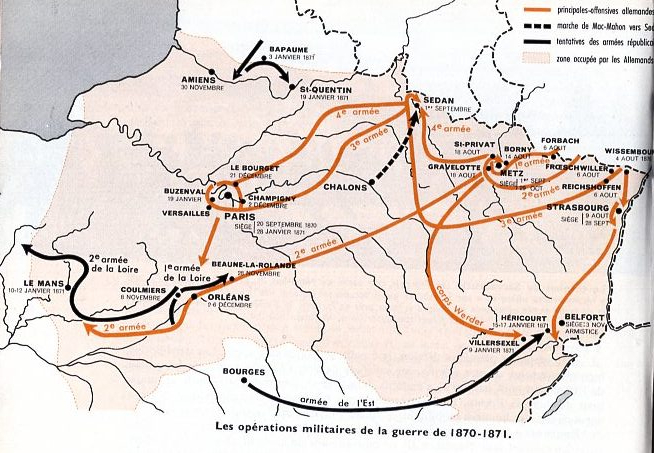

France and Prussia rapidly mobilized their respective armies on July 15, 1870. The next day, the French parliament declared war on Prussia and sent it formal notice several days later. By the first days of August 1870, both France and Germany had crossed each other’s borders in the Alsace-Lorraine region (along France’s northeast; see map). An early French offensive soon threatened Saarland.

But Napoleon III badly underestimated the Prussians and overestimated his own strength. He had hoped that Austria (Prussia’s rival for German hegemony), Denmark and Italy (in pursuit of their own national interests) would give him aid; but they just stood aside. Bismarck’s army turned out to be much better-trained, and able to maximize its political and technical home base. It mobilized 470,000 in just over a week and advanced 22 km a day, while France took three weeks to mobilize 300,000 and advanced only 9 km a day. Less than a month into the war, the French offensive quickly faltered and shifted to the defensive, while the Prussians won major battles in quick succession.

In France, the government on Aug. 10-11 hastily created a Garde Mobile (Mobile Guard), and drafted into it all single men and childless widowers not already in the main armies. All the other remaining male citizens above 18 were enlisted into a reserve Garde Nationale (National Guard), with its battalions organized as local units that remained in their home districts.

The attitude of the workers’ movement on the war. The French and German workers and other toiling masses were generally opposed to the war. Their anti-war attitude was reflected and amplified in propaganda and mass campaigns of the International Workingmen’s Association (First International, founded in London in 1864 and led by Karl Marx). The International was growing more popular and had growing national sections throughout Europe despite persecution by the French, German, and other states.

Although he was in British exile, Marx utilized all available means of communication to follow every twist and turn of the war, and shared his analysis with the rest of the International. Starting with his address of the General Council on the declaration of war, his series of communications to the workers’ movement through the International and the press were spread widely throughout France, Germany and elsewhere.

Shortly before war was declared, the Paris section of the International launched antiwar protests. Napoleon III in turn had his gendarmes raid its French branches and arrest 60 of its leading activists. Nevertheless, the International continued its antiwar campaign throughout France.

As for the German working class, Marx and Engels recognized that they could join the nationalist groundswell “so long as it is limited to the defense of Germany” and differentiated “between German national interests and those of the dynastic Prussians.” The leaders of the International called on the German workers to oppose the annexation of Alsace-Lorraine and to work for “an honorable peace for France” under a democratic-republican government that would replace the Bonapartist regime.

Marx reminded the German workers that if they were to “allow the present war to lose its strictly defensive character and to degenerate into a war against the French people, victory or defeat will prove alike disastrous.” He also predicted that, however the war turned out, “the death knell of the Second Empire has already sounded at Paris. It will end, as it began, by a parody.”

When the North German parliament voted on war credits, Liebknecht and Bebel (also members of the International) filed a protest vote of abstention. They joined a German workers’ conference, which issued a resolution denouncing the war and called on the German workers and democrats to join the antiwar protests. Similar resolutions were adopted in mass meetings in Berlin and many other major German cities.

The French defeat at Sedan, Napoleon’s surrender, and his Empire’s collapse. On August 18, the Prussian forces won another decisive battle at Gravelotte. They trapped the battered French Army of the Rhine (113,000 men under Gen. Bazaine) at Metz and began to lay siege. The other French Army of Châlons, 103,000-strong and personally led by Napoleon himself, attempted to break the siege. But on Aug. 30, it was caught in a giant pincer attack by the 250,000-strong Prussian Third and Fourth Armies.

The Emperor’s army was trapped in the vicinity of Sedan, and was shredded to pieces throughout the day of Sept. 1. Napoleon offered surrender, which the Prussian command formally accepted the next day. He and his surviving 84,000 troops were taken into captivity.

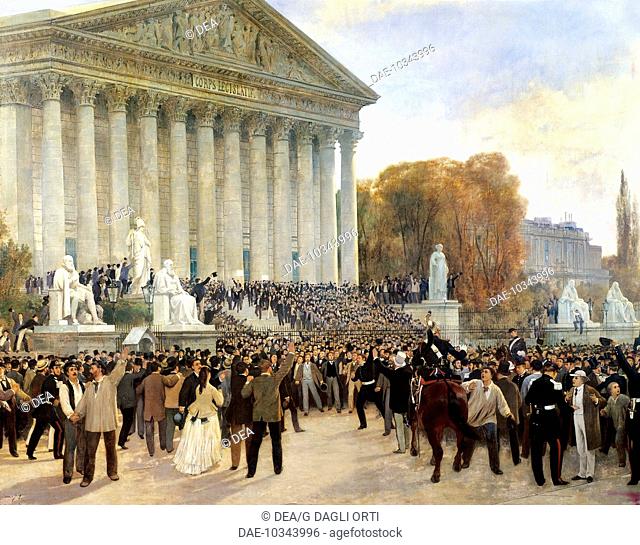

Back in Paris, the news of the Sedan defeat and Napoleon’s surrender fired up the masses, now armed and organized as National Guard units. On Sept. 4, a big crowd led by National Guard riflemen stormed the Palais Bourbon and took over the Chamber of Deputies. The French Second Empire collapsed in a whimper.

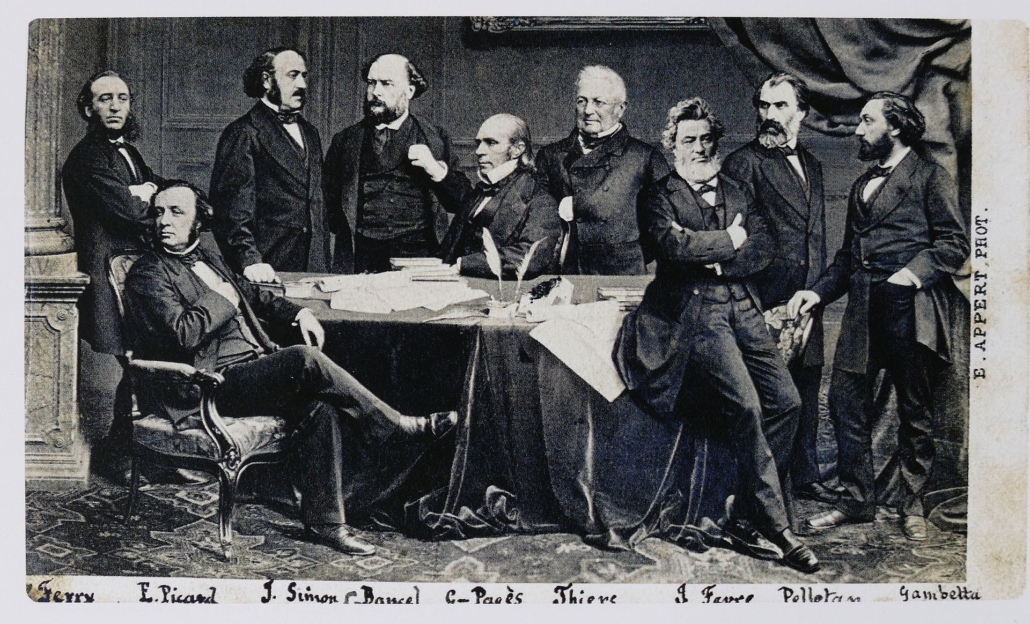

The Third Republic under the Government of National Defense. That same day, leading members of the Chamber (which only had limited powers under Napoleon) gathered at the historic Hôtel de Ville that housed the Paris Town Hall. There they declared the Third Republic, and set up a Government of National Defense to continue the now-defensive war. The new government, with monarchist General Louis Trochu as head, was dominated by conservative republicans and double-faced monarchists.

Marx hailed the creation of the new Republic but weighed its prospects with misgivings. In the second address of the General Council of the International (Sept. 9), he noted that this Republic was in the hands of a government “composed partly of notorious Orleanists [former king Louis-Philippe’s supporters], partly of middle-class Republicans.” On the other hand, he reminded the French workers not to set itself the aim of overthrowing the government (“a desperate folly”) but to proceed with “the organization of their own class” for longer-term goals.

Indeed, Marx had the insight to see that the French proletariat was not yet ready to seize power nationwide, even as it had to confront the new “Government of National Defense” as the latest incarnation of the French bourgeois state sworn to preserve capitalist rule. This state intended to block proletarian power that was brewing in Paris, even bow down to Prussia if it came to that.

The International’s second manifesto called for German working-class demonstrations to end the war, to recognize the French Republic and reach an “honorable peace,” and to oppose the annexation of Alsace-Lorraine. But the German social-democrats who signed the manifesto were promptly arrested and dragged to prison in chains. Liebknecht and Bebel, the main anti-war advocates within the German parliament, were also arrested for high treason. Thus, the mass agitation for peace was drowned by the ultra-nationalist German urge for more territory; Prussian armies thrust deeper into France.

With the bulk of its main armies disabled at Metz and Sedan, the new French government scrounged around to gather all types of military units, including raw Mobile Guard conscripts and the localized National Guard, in order to strengthen the defenses around Paris. It fortified the city and built up enormous stocks of food and ammunition to last the duration of the expected siege.

Paris standing alone but armed. Traditionally, the National Guard was a middle-class-dominated militia that was supposed to fight together with the Mobile Guard (likewise middle-class-dominated) in support of the main French armies (which were predominantly recruited from the peasant masses), and to undertake police tasks as well.

But now, with the capital in danger of Prussian attack, impoverished Parisian masses swelled the National Guard’s ranks to a total of 330,000 men. To its 60 old battalions were added 130 newly created battalions. They were paid 30 sous (1 franc 50) per day, and armed with the same infantry rifles and guns carried by the regular army. The Paris public also paid for 400 bronze cannons for its National Guard units.

By Sept. 18, German forces completely surrounded Paris, cut it off from the rest of unoccupied France, and began to lay siege. The National Assembly had left Paris earlier, moving to Bordeaux nearly 600 km to the south. The minister of the interior Léon Gambetta escaped by hot-air balloon to the city of Tours some 300 km to the south, with a mandate to raise a new Army of the Loire and direct the war effort from there.

In effect, the French government had two distant arms that barely coordinated with each other—Gambetta in Tours, the National Assembly in Bordeaux—and both were cut off from the besieged capital and its governor, General Trochu (also overall military commander for the defense of Paris, and nominal President).

3. How did the bungling Government of National Defense handle the Paris siege and trigger the Paris Commune?

The siege of Paris. While the hastily raised French armies of Gambetta were being defeated on most fronts, the people of Paris and their National Guard battalions braced for the worst. With Gambetta and the National Assembly too detached from Paris, Jules Favre (as vice president and foreign minister) and Adolphe Thiers, another conservative republican with monarchist links, became the Government’s de facto leaders. They were more concerned about the rebellious city than about the enemy knocking at its gates.

For most Parisians, food stocks were starting to run out while disease stalked the poor neighborhoods under severe winter conditions. Many of the wealthy, on the other hand, were able to retain their comforts by escaping to safety through the Prussian lines or by replenishing their supplies at sky-high prices. The people grew more frustrated at the Government for its incompetence, cowardice, and signs of capitulationism. They were in fact on the brink of revolt.

On Oct. 27, 1870, the French army trapped in Metz under Gen. Bazaine surrendered without a fight. News spread that the real political leaders of the Government (Favre and Thiers) were in fact negotiating with the Prussians for a peace that would disarm Paris. Outraged Parisians massed in the streets and called it a “government of national betrayal.”

On Oct. 31, crowds backed by worker-dominated National Guard units stormed the Town Hall and temporarily ousted the Government. But middle-class battalions quickly came to the Government’s rescue. To avoid civil war and preserve French unity against the Prussian siege, Auguste Blanqui and other leaders of the uprising withdrew. The Government promised to hold elections. But instead it held a plebiscite on its continuance—which it handily won. It then proceeded to arrest 25 leaders of the Blanquist-led uprising. (Blanqui himself would be captured on the eve of the Paris Commune and remain prisoner beyond its fall.)

The people scoffed at the Paris military governor, General Trochu, who publicly vowed “not to cede an inch” but privately said from the outset that any defense of Paris was “heroic folly.” He came up with a very passive “defense plan,” and failed to unite the various Guard forces and armed civilians who were ready to fight. Increasingly, the people blamed the Government for the bungled conduct of the war.

In defending the besieged city, the people began to place more hope on their National Guard units, which were ill-trained although well-armed. As more and more rich and middle-class people left the city for safer sanctuaries, most of Paris arrondisements (local districts) and their National Guard units turned increasingly proletarian and radicalized. The battalions were commanded by officers who were elected by the rank and file troops themselves. Some National Guard units were led by socialist workers and members of the International. Often on the initiative of women (who were excluded from National Guard duty), the masses organized themselves, converted public halls and theaters into soup kitchens and Red Club centers, which housed refugees and became the regular venues for daily discussions.

French military units and armed workers had tried to break the Prussian siege twice (in November 1870 and January 1871) but both ended in disaster. Massive daily bombardment by Prussian artillery began, battering the city for 23 days. On Jan. 18, on the outskirts of Paris, Versailles fell to the Prussians. The new German Empire was formally proclaimed, and its emperor Wilhelm crowned, in its Hall of Mirrors. When General Trochu’s Jan. 19 sortie failed to break the siege and incurred terrible French casualties, he resigned as Paris governor. Thiers and Favre remained as the real Government decision-makers; they quickly prepared to capitulate.

French surrender, rise of Thiers regime. On Jan. 28, 1871, the French Government signed an armistice with Prussia. Favre (on behalf of France) and Bismarck (on behalf of Emperor Wilhelm) signed the Convention defining the terms of armistice and capitulation. The humiliating terms included the payment of huge amounts of French money for indemnity and war reparations.

Upon Prussia’s urging that France quickly set up a new government to legitimately ratify the peace treaty, national elections were held on Feb. 8. (All male citizens were allowed to vote, but women were not.) The vast mass of rural electors, attracted to the slogan “peace at any price” and still charmed by the old nobility, were swayed to support monarchism and reject the intransigence of radical and proletarian Paris. They chose a new government overwhelmingly composed of monarchist, capitalist, middle-class, cleric and landed-gentry deputies.

Of the Assembly’s 750 deputies, fully 450 were diehard monarchists and Bonapartists; the rest were conservative republicans, and only about 100 were radical republicans. One-third of the deputies had titles of nobility. On Feb. 12, the Assembly elected Adolphe Thiers as president and chief executive. On Feb. 26, it ratified the treaty with Prussia, putting the final seal on the onerous peace terms. The treaty required France to cede Alsace and part of Lorraine to Germany, and to pay 5 billion gold francs as war reparations.

Sensing the rebellious pulse of Paris, Bismarck decided to march his Prussian troops into the city on March 1 but only for a brief and symbolic two-day occupation. He astutely decided not to fully occupy it, only to guard its eastern approaches, and let the French shoulder the task of keeping order within the city through National Guard units. But this decision had its consequences. As Engels noted: “The forts were surrendered, the city wall stripped of guns, the weapons of the regiments of the line and of the Mobile Guard were handed over, and they themselves considered prisoners of war. But the National Guard kept its weapons and guns…”

The Thiers regime appointed monarchists as high functionaries. It appointed its own choices as National Guard commander (the Jesuit general de Paladine), Paris police prefect (the Bonapartist Valenin), and for other key military posts. It sentenced August Blanqui to death (later commuted to life sentence) as leader of the Oct. 31 uprising. It suppressed six Republican papers for preaching “sedition and disobedience to the laws.”

On March 10-12, the Assembly passed four laws that further crippled Paris. (It also imposed other new financial measures, in an effort to squeeze the French people dry to pay war reparations and hopefully to persuade the German occupiers to leave earlier.)

- First, it slashed the pay of National Guard troops to almost nil, leaving them penniless since the ruined economy could not provide them other incomes.

- Second, it lifted the moratorium on the sale of goods at pawnshops, where many workers had pawned their meager valuables.

- Third, it required all bills overdue for the past four months to be paid unconditionally and with interest within the next three days—many of them unpaid rents of over 200,000 workers’ households.

- And as a fourth and final humiliation, the new government decided to move its national seat to Versailles, just 17 km outside Paris and directly under Prussian eyes.

These measures further fueled the growing resentment of the workers and other toiling masses, and began to ruin even lower middle-class livelihoods. The tinderbox was about to explode into the historic Paris Commune. It would also spread across France through more short-lived armed uprisings in several other cities. # (Read Part II) (Read Part III)

Corrections on 2021-04-16, with additions in bold/red:

- “Capitalist and employer abuses” was added to the French working-class woes.

- “Paris, in particular, already had a long history of uprisings by workers and lower-middle classes since the 1790s.” (rather than 1830s.)

- “Marx had the insight to see that the French proletariat was not yet ready to seize power nationwide, …”

- It sentenced August Blanqui to death (later commuted to life sentence) as leader of the Oct. 31 uprising. (in lieu of “… to death a Blanquist …”

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!